ProPublica

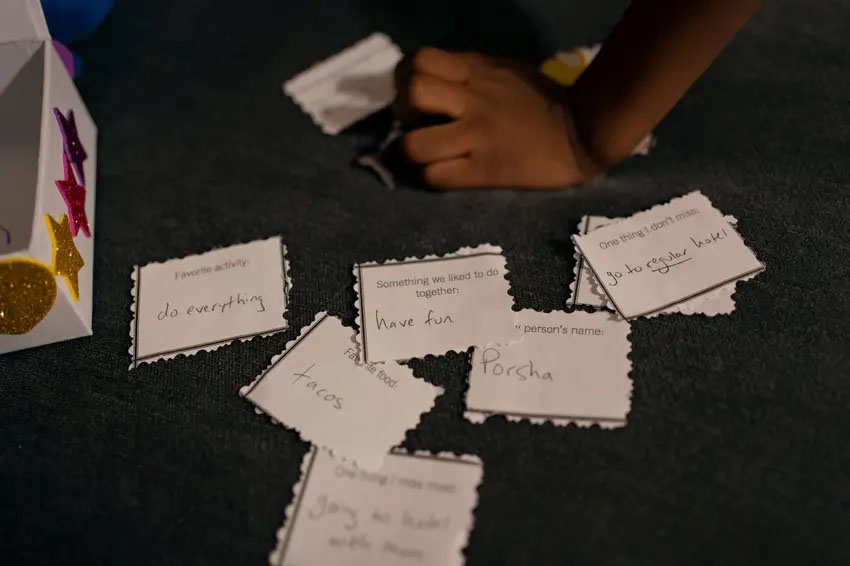

(The Texas Tribune ) –Hope Ngumezi marveled at the energy [his wife,] Porsha had for their two sons, ages 5 and 3. Whenever she wasn’t working, she was chasing them through the house or dancing with them in the living room. As a finance manager at a charter school system, she was in charge of the household budget. As an engineer for an airline, Hope took them on flights around the world – to Chile, Bali, Guam, Singapore, Argentina.

The two had met at Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas.

“When Porsha and I began dating,” Hope said, “I already knew I was going to love her.”

She was magnetic and driven, going on to earn an MBA, but she was also gentle with him, always protecting his feelings. Both were raised in big families, and they wanted to build one of their own.

When he learned Porsha was pregnant again in the spring of 2023, Hope wished for a girl. Porsha found a new OB-GYN who said she could see her after 11 weeks. Ten weeks in, though, Porsha noticed she was spotting. Over the phone, the obstetrician told her to go to the emergency room if it got worse.

To celebrate the end of the school year, Porsha and Hope took their boys to a water park in Austin, and as they headed back, on June 11, Porsha told Hope that the bleeding was heavier. They decided Hope would stay with the boys at home until a relative could take over; Porsha would drive to the emergency room at Houston Methodist Sugar Land, one of seven community hospitals that are part of the Houston Methodist system.

At 6:30 p.m., three hours after Porsha arrived at the hospital, she saw huge clots in the toilet. “Significant bleeding,” the emergency physician wrote.

“I’m starting to feel a lot of pain,” Porsha texted Hope.

Around 7:30 p.m., she wrote, “She said I might need surgery if I don’t stop bleeding,” referring to the nurse.

At 7:50 p.m., after a nurse changed her second diaper in an hour, “Come now.”

Still, the doctor didn’t mention a D&C at this point, records show. Medical experts told ProPublica that this wait-and-see approach has become more common under abortion bans. Unless there is “overt information indicating that the patient is at significant risk,” hospital administrators have told physicians to simply monitor them, said Dr. Robert Carpenter, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist who works in several hospital systems in Houston. Methodist declined to share its miscarriage protocols with ProPublica or explain how it is guiding doctors under the abortion ban.

As Porsha waited for Hope, a radiologist completed an ultrasound and noted that she had “a pregnancy of unknown location.” The scan detected a “sac-like structure” but no fetus or cardiac activity. This report, combined with her symptoms, indicated she was miscarrying.

But the ultrasound record alone was less definitive from a legal perspective, several doctors explained to ProPublica. Since Porsha had not had a prenatal visit, there was no documentation to prove she was 11 weeks along. On paper, this “pregnancy of unknown location” diagnosis could also suggest that she was only a few weeks into a normally developing pregnancy, when cardiac activity wouldn’t be detected. Texas outlaws abortion from the moment of fertilization; a record showing there is no cardiac activity isn’t enough to give physicians cover to intervene, experts said.

Dr. Gabrielle Taper, who recently worked as an OB-GYN resident in Austin, said that she regularly witnessed delays after ultrasound reports like these.

“If it’s a pregnancy of unknown location, if we do something to manage it, is that considered an abortion or not?” she said, adding that this was one of the key problems she encountered.

After the abortion ban went into effect, she said, “there was much more hesitation about: When can we intervene, do we have enough evidence to say this is a miscarriage, how long are we going to wait, what will we use to feel definitive?”

At Methodist, the emergency room doctor reached Davis, the on-call OB-GYN, to discuss the ultrasound, according to records. They agreed on a plan of “observation in the hospital to monitor bleeding.”

Around 8:30 p.m., just after Hope arrived, Porsha passed out. Terrified, he took her head in his hands and tried to bring her back to consciousness. “Babe, look at me,” he told her. “Focus.” Her blood pressure was dipping dangerously low. She had held off on accepting a blood transfusion until he got there. Now, as she came to, she agreed to receive one and then another.

By this point, it was clear that she needed a D&C, more than a dozen OB-GYNs who reviewed her case told ProPublica. She was hemorrhaging, and the standard of care is to vacuum out the residual tissue so the uterus can clamp down, physicians told ProPublica.

“Complete the miscarriage and the bleeding will stop,” said Dr. Lauren Thaxton, an OB-GYN who recently left Texas.

“At every point, it’s kind of shocking,” said Dr. Daniel Grossman, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, San Francisco who reviewed Porsha’s case. “She is having significant blood loss and the physician didn’t move toward aspiration.”

All Porsha talked about was her devastation of losing the pregnancy. She was cold, crying and in extreme pain. She wanted to be at home with her boys. Unsure what to say, Hope leaned his chest over the cot, passing his body heat to her.

At 9:45 p.m., Esmeralda Acosta, a nurse, wrote that Porsha was “continuing to pass large clots the size of grapefruit.” Fifteen minutes later, when the nurse learned Davis planned to send Porsha to a floor with fewer nurses, she “voiced concern” that he wanted to take her out of the emergency room, given her condition, according to medical records.

At 10:20 p.m., seven hours after Porsha arrived, Davis came to see her. Hope remembered what his mother had told him on the phone earlier that night, “She needs a D&C.” The doctor seemed confident about a different approach: misoprostol. If that didn’t work, Hope remembers him saying, they would move on to the procedure.

A pill sounded good to Porsha because the idea of surgery scared her. Davis did not explain that a D&C involved no incisions, just suction, according to Hope, or tell them that it would stop the bleeding faster. The Ngumezis followed his recommendation without question.

“I’m thinking, ‘He’s the OB, he’s probably seen this a thousand times, he probably knows what’s right,’” Hope said.

But more than a dozen doctors who reviewed Porsha’s case were concerned by this recommendation. Many said it was dangerous to give misoprostol to a woman who’s bleeding heavily, especially one with a blood clotting disorder.

“That’s not what you do,” said Dr. Elliott Main, the former medical director for the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative and an expert in hemorrhage, after reviewing the case. “She needed to go to the operating room.”

Main and others said doctors are obliged to counsel patients on the risks and benefits of all their options, including a D&C.

Performing a D&C, though, attracts more attention from colleagues, creating a higher barrier in a state where abortion is illegal, explained Goulding, the OB-GYN in Houston. Staff are familiar with misoprostol because it’s used for labor, and it only requires a doctor and a nurse to administer it.

To do a procedure, on the other hand, a doctor would need to find an operating room, an anesthesiologist and a nursing team.

“You have to convince everyone that it is legal and won’t put them at risk,” said Goulding. “Many people may be afraid and misinformed and refuse to participate – even if it’s for a miscarriage.”

Davis moved Porsha to a less-intensive unit, according to records. Hope wondered why they were leaving the emergency room if the nurse seemed so worried. But instead of pushing back, he rubbed Porsha’s arms, trying to comfort her. The hospital was reputable.

“Since we were at Methodist, I felt I could trust the doctors.”

On their way to the other ward, Porsha complained of chest pain. She kept remarking on it when they got to the new room. From this point forward, there are no nurse’s notes recording how much she continued to bleed.

“My wife says she doesn’t feel right, and last time she said that, she passed out,” Hope told a nurse.

Furious, he tried to hold it together so as not to alarm Porsha.

“We need to see the doctor,” he insisted.

Her vital signs looked fine. But many physicians told ProPublica that when healthy pregnant patients are hemorrhaging, their bodies can compensate for a long time, until they crash. Any sign of distress, such as chest pain, could be a red flag; the symptom warranted investigation with tests, like an electrocardiogram or X-ray, experts said. To them, Porsha’s case underscored how important it is that doctors be able to intervene before there are signs of a life-threatening emergency.

But Davis didn’t order any tests, according to records.

Around 1:30 a.m., Hope was sitting by Porsha’s bed, his hands on her chest, telling her, “We are going to figure this out.” They were talking about what she might like for breakfast when she began gasping for air.

“Help, I need help!” he shouted to the nurses through the intercom. “She can’t breathe.”

Hours later, Hope returned home in a daze.

“Is mommy still at the hospital?” one of his sons asked.

Hope nodded; he couldn’t find the words to tell the boys they’d lost their mother. He dressed them and drove them to school, like the previous day had been a bad dream. He reached for his phone to call Porsha, as he did every morning that he dropped the kids off. But then he remembered that he couldn’t.

Friends kept reaching out. Most of his family’s network worked in medicine, and after they said how sorry they were, one after another repeated the same message.

All she needed was a D&C, said one. They shouldn’t have given her that medication, said another.

It’s a simple procedure, the callers continued. We do this all the time in Nigeria.

Next week, read part III: Doctors reach for riskier miscarriage treatments.